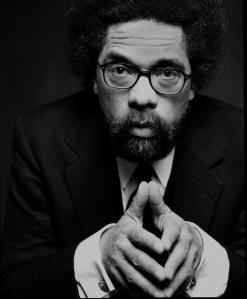

Dr. Cornel Ronald West defies simple description. He is a leading philosopher, author, and academic with an Ivy League resume, but he is also a hip-hop artist, a prominent activist for the African-American community, and a self-proclaimed prophet. In all of his many roles, Dr. West is a man with considerable public influence. He is famous almost as much for his public feuds as he is for his provocative theories on race and class oppression in the United States. Since Dr. West published his bestselling book Race Matters in 1994, cementing himself as a leading public intellectual, he has had many disagreements with other public figures and been subject to much criticism. West’s persona (and to some degree, his celebrity) is built on him being unapologetic, attention-grabbing, and, according to many of his critics, increasingly outrageous.

Dr. Cornel Ronald West defies simple description. He is a leading philosopher, author, and academic with an Ivy League resume, but he is also a hip-hop artist, a prominent activist for the African-American community, and a self-proclaimed prophet. In all of his many roles, Dr. West is a man with considerable public influence. He is famous almost as much for his public feuds as he is for his provocative theories on race and class oppression in the United States. Since Dr. West published his bestselling book Race Matters in 1994, cementing himself as a leading public intellectual, he has had many disagreements with other public figures and been subject to much criticism. West’s persona (and to some degree, his celebrity) is built on him being unapologetic, attention-grabbing, and, according to many of his critics, increasingly outrageous.

West has risen to the status of a public intellectual for his “brilliance and ability to articulate the complex lived experience of African-Americans”, but it can be difficult to separate his achievements from his antics (Hayes 75). His primary conflict as a public intellectual is in balancing the dual role of being both public, and being intellectual. In the public sphere, his intellectualism is often eclipsed by his persona and his desire for recognition. The incredible genius of Dr. West is always there—in his electrifying speeches, in his impressive academic writing, and in his thoughtful sociocultural commentary—but it is much harder to realize beneath the behemoth shadow of his public self.

From an early age, Cornel West exhibited the qualities that would define his life: a commitment to Christianity, a passion for racial justice, and sheer intelligence. Growing up in Sacramento, CA, though he is a native of Tulsa, OK, West was heavily inspired by the Baptist church that he attended in his youth (Encyclopedia Brittanica 1). His encyclopedia biography explains that:

“…West regularly attended services at the local Baptist church, where he listened to moving testimonials of privation, struggle, and faith from parishioners whose grandparents had been slaves.”

The religious convictions of African-Americans, and the long tradition of the black church, informed West’s own faith and likely set the stage for his later theological studies.

Equally as big an influence as the Church was the growing power of the Black Panther Party, which impressed and inspired young West. He learned about the importance of local political activism and community building from the Black Panthers (Dartmouth University 1). At a young age, West engaged in political activism by refusing to salute the American flag in protest of the second-class treatment of African-Americans in the United States (Dartmouth University 1). Importantly, and tellingly for his future, West never separated his religious ideals from his political ideals. He found in one a continuance of the other, and thus combined and strengthened both his Christianity and his commitment to social justice.

Academically, young Cornel West excelled, entering Harvard University on a scholarship at just 17 years old, and graduating magna cum laude three years later (Encyclopedia Brittanica 1). Always seeking to expand his knowledge, he earned a PhD in Philosophy at Princeton University in 1980 and then launched his career as an academic (Dartmouth University 1). In the years following, Dr. West ascended the ladder of higher educational institutions. He taught classes on religion, African-American politics, and philosophy at Yale, Harvard, the University of Paris, and Princeton (“About Dr. Cornel West” 1). In 1994, following the Rodney King riots in LA and amidst much racial turbulence nationwide, Dr. West published his most popular book, Race Matters. The book is a collection of essays about the ongoing race debate in America, toppling topics like black sexuality, the absence of black leadership, and the relations between African Americans and other minorities (West 1). A national bestseller, Race Matters catapulted Dr. West into the national spotlight.

In Race Matters, Dr. West advances theories that significantly informed the national dialogue about race. He presents the idea of “black nihilism”, describing how African American communities suffer from a “breakdown of traditional social institutions..and the concomitant growth of hopelessness, lovelessness, and meaningless, particularly among the black urban dispossessed” (Hayes 76). According to West, the despair of the black urban poor helps contribute to their oppression. In his own words, West states,

“the major enemy of black survival in America has been and is neither oppression nor exploitation but rather the nihilistic threat—that is, loss of hope and absence of meaning. For as long as hope remains and meaning is preserved, the possibility of overcoming oppression stays alive.” (West, “Race Matters”)

The principle of black nihilism is rooted in West’s Christian beliefs and his pragmatic philosophy. It also harkens back to his impressions from the Black Panther Party, specifically the belief in the importance of community building. The nihilism theory resonated particularly with African-Americans who could relate to the long-held feelings of hopelessness and futility that West described. In the book, West also distinctly suggests that black nihilism is caused by an absence of black political and intellectual leadership (Hayes 76). He is very critical of America’s most famous black leaders and he strongly suggests that we need better leaders in order to uplift the black community. In that way, his theory is somewhat conservative because it places responsibility and agency with the minority to improve their own condition, rather than solely with the overarching system. However, West also recognizes that the system itself is oppressive, and in Race Matters he criticizes black conservatives for blaming poor black people for their predicament (Hayes 76). He is thus able to offer both liberal and conservative critiques by acknowledging the breakdown in the African-American psyche while also being careful not to blame African-Americans for their own oppression. In a quote from the book, West eloquently says,

“We indeed must criticize and condemn immoral acts of black people, but we must do so cognizant of the circumstances into which people are born and under which they live” (West, “Race Matters”).

While not everyone agreed with Dr. West’s theories, he became very popular for his multi-faceted critique and for remaining grounded in his Christian morals. The race debate in America had long been very divided and polarized between liberals and conservatives, blacks and whites, but West helped reinvigorate the conversation by promoting theories that crossed partisan and racial lines. Above all else, his book firmly established the idea, on a national platform, that race is important and that it matters in American society.

After the 1994 publication of Race Matters, West’s status as a public intellectual grew. Over the next decade, he became a frequent guest on CNN, C-Span, and shows like the Bill Maher Show (“Dr Cornel West” 1). He continued to engage in activism and create new academic works, including another popular 2004 book called Democracy Matters, in which he describes the damaging imperialism and nihilism present in our democracy (Malkani 117). Yet as his celebrity grew, Dr. West forayed more and more away from his scholarly work, ultimately leading some to question his actions.

According to Michael Eric Dyson, another leading African American public intellectual, Dr. West has experienced a scholarly decline in the years since becoming famous. His music ventures, including a hip-hop spoken word album released in 2001, were seen by some as vain efforts to garner attention for himself. In 2002, West had a position at Harvard University, and he was admonished by then-President Lawrence Summers for devoting too much time to his side ventures (Dyson 1). Whether President Summers’ criticism of West is merited is difficult to say, but it does show that some people were displeased with West’s evolution as his popularity grew.

Perhaps most damaging of all to Dr. West’s credibility, he has been incredibly vocal of his dislike for and disapproval of President Obama. Once a strong supporter of Obama’s presidential campaign, Dr. West has since criticized the president for being a “Rockefeller Republican in Blackface”, a “neoliberal opportuntist”, a non-progressive, and generally for not being serious about issues of injustice and equality (Dyson 1). West claims that he is unhappy with Obama’s performance as president, but others suggest that he is jealous of the success of the first black president, or simply feeling snubbed by the fact that Obama did not pander to West once he reached office (Dyson 1). Either way, West’s public bashing of Obama has been so severe and lacking in respect that it borders on irrational. Thinking back to some of West’s earlier theories from Race Matters, he has long disliked and criticized black leadership, so it makes sense that he would criticize Obama. Still, his failure to respect the first black president is damaging to his image.

In addition to attacking Obama, West has also criticized MSNBC’s Melissa Harris-Parry, and African-American activist giants like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. Dyson shows how West often invokes the same arguments in criticizing prominent black figures–suggesting that they are puppets for the white patriarchal system. In the case of Sharpton, for instance, West labeled him as the “head house negro on the Obama plantation” (Dyson 1). Such attacks attempt to diminish the authenticity of other black public intellectuals, and simultaneously seek to uplift West, who in comparison can present himself as the only true fighter for the black cause. West’s attacks on others have led to deepening ideological rifts with his contemporaries, including Dyson, who was once West’s mentee and longtime friend. West and Dyson had a falling out in 2012, when West launched his familiar attack against Dyson, claiming that he was a pawn in the Obama administration (Dyson 1).

This is all to say that Dr. West struggles as a public figure because, at the end of the day, he has an unquenchable thirst to be recognized and appreciated. All of Dr. West’s public actions in recent years have been self-serving, even tearing others down in order to make himself look more like the black prophet and revolutionary that he imagines himself to be. An article in New York Magazine put it best, saying that West’s “greatest flaw” is “his hunger for adulation” (Miller 1). This egotistical desire for recognition underlies his many disputes, bouts of self-righteousness, and unsubstantiated attacks on others.

West would serve himself well to heed the words of blogger and author Stephen Mack. In his blog post “The “Decline of the Public Intellectual (?)”, Mack states that, “…we need to be more concerned with the work public intellectuals must do, irrespective of who happens to be doing it.” The public should be able to talk less about Dr. West’s egotisms and more about his ideas. West misunderstands his function in society as a public intellectual. His desire to be famed and appreciated is not part of his duty. It is the public intellectual’s job to ensure that the audience is hearing things worth talking about—and that does not include personally motivated attacks against the President, or some future album of Cornel West reggae music. West would do well to divulge his public intellectual work from his ego.

Dr. West can, and has, put forth insightful and intellectual contributions to the public discourse on race. He has the platform he always wanted, but the central key is how he uses it.

Works Cited

“About Dr. Cornel West” Dr. Cornel West – Offical Website. http://www.cornelwest.com/bio.html#.Vf47-lpCZlJ

“Cornel West”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2015. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Cornel-West

“Cornel West Biography.” Dartmouth.edu. Dartmouth University. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~dof/pdfs/Cornel_West_bio.pdf

Dyson, Michael Eric. “The Ghost of Cornel West.” New Republic. The New Republic. 19 Apr. 2015. http://www.newrepublic.com/article/121550/cornel-wests-rise-fall-our-most-exciting-black-scholar-ghost

Hayes III, Floyd W.”Review: Cornel West on Social Justice” The Journal of African American History. Vol. 89, No. 1 (Winter, 2004), pp. 75-79 http://www.jstor.org.libproxy1.usc.edu/stable/4134047

Mack, Stephen. “The New Democratic Review: The “Decline” of the Public Intellectual (?).” The New Democratic Review: The “Decline” of the Public Intellectual (?). 30 Aug. 2015. http://www.stephenmack.com/blog/archives/2015/08/the_decline_of_11.html#more

Miller, Lisa. “Why Cornel West Can’t Seem to Find Love and Justice in His Own Life.” NYMag.com. New York Media LLC. 06 May 2012. http://nymag.com/news/features/cornel-west-2012-5/

Malkani, Sara. “Review: Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism by Cornel West” Pakistan Horizon. Vol. 58, No. 3 (July 2005), pp. 117-120 http://www.jstor.org.libproxy1.usc.edu/stable/41394106

West, Cornel. Race Matters. Boston: Beacon Press, 1993.